About the EPI

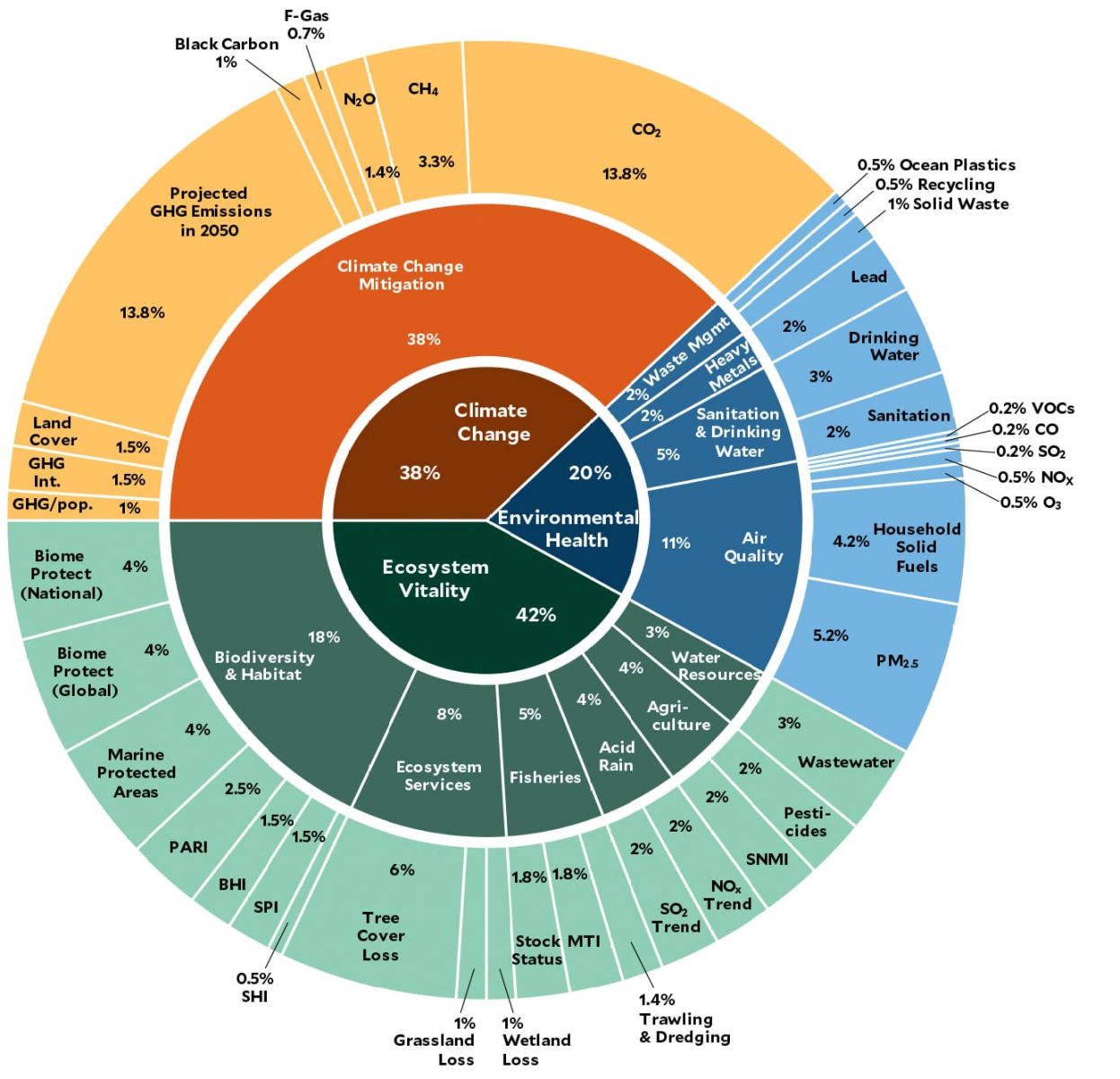

The 2022 Environmental Performance Index (EPI) provides a data-driven summary of the state of sustainability around the world. Using 40 performance indicators across 11 issue categories, the EPI ranks 180 countries on climate change performance, environmental health, and ecosystem vitality. These indicators provide a gauge at a national scale of how close countries are to established environmental policy targets. The EPI offers a scorecard that highlights leaders and laggards in environmental performance and provides practical guidance for countries that aspire to move toward a sustainable future.

EPI indicators provide a way to spot problems, set targets, track trends, understand outcomes, and identify best policy practices. Good data and fact-based analysis can also help government officials refine their policy agendas, facilitate communications with key stakeholders, and maximize the return on environmental investments. The EPI offers a powerful policy tool in support of efforts to meet the targets of the UN Sustainable Development Goals and to move society toward a sustainable future.

Overall EPI rankings indicate which countries are best addressing the environmental challenges that every nation faces. Going beyond the aggregate scores and drilling down into the data to analyze performance by issue category, policy objective, peer group, and country offers even greater value for policymakers. This granular view and comparative perspective can assist in understanding the determinants of environmental progress and in refining policy choices.

Funding from the the McCall MacBain Foundation of Canada supports the EPI work at both Yale and Columbia. The EPI research team is deeply grateful for this generous support.

Suggested Citation:

Wolf, M. J., Emerson, J. W., Esty, D. C., de Sherbinin, A., Wendling, Z. A., et al. (2022). 2022 Environmental Performance Index. New Haven, CT: Yale Center for Environmental Law & Policy. epi.yale.edu

Explaining Performance

A number of striking conclusions emerge from the EPI rankings and indicators. First, good policy results are associated with wealth (GDP per capita), meaning that economic prosperity makes it possible for nations to invest in policies and programs that lead to desirable outcomes. This trend is especially true for issue categories under the umbrella of environmental health, as building the necessary infrastructure to provide clean drinking water and sanitation, reduce ambient air pollution, control hazardous waste, and respond to public health crises yields large returns for human well-being.

Second, the pursuit of economic prosperity – manifested in industrialization and urbanization – often means more pollution and other strains on ecosystem vitality, especially in the developing world, where air and water emissions remain significant. But at the same time, the data suggest countries need not sacrifice sustainability for economic security or vice versa. In every issue category, we find countries that rise above their economic peers. Policymakers and other stakeholders in these leading countries demonstrate that focused attention can mobilize communities to protect natural resources and human well-being despite the strains associated with economic growth. In this regard, indicators of good governance – including commitment to the rule of law, a vibrant press, and even-handed enforcement of regulations – have strong relationships with top-tier EPI scores.

Third, while top EPI performers pay attention to all areas of sustainability, their lagging peers tend to have uneven performance. Denmark, which ranks #1, has strong results across most issues and with leading-edge commitments and outcomes with regard to climate change mitigation. In general, high scorers exhibit long-standing policies and programs to protect public health, preserve natural resources, and decrease greenhouse gas emissions. The data further suggest that countries making concerted efforts to decarbonize their electricity sectors have made the greatest gains in combating climate change, with associated benefits for ecosystems and human health. We note, however, that every country – including those at the top of the EPI rankings – still has issues to improve upon. No country can claim to be on a fully sustainable trajectory.

Fourth, laggards must redouble national sustainability efforts along all fronts. A number of important countries in the Global South, including India and Nigeria, come out near the bottom of the rankings. Their low EPI scores indicate the need for greater attention to the spectrum of sustainability requirements, with a high-priority focus on critical issues such as air and water quality, biodiversity, and climate change. Some of the other laggards, including Nepal and Afghanistan, face broader challenges such as civil unrest, and their low scores can almost all be attributed to weak governance.

Refining metrics

Ongoing advancements in environmental monitoring and data reporting enable the 2022 EPI to introduce several innovative indicators. The 2022 EPI supports evolving climate policy discussions with a new indicator that projects countries’ progress towards net-zero emissions in 2050. The net-zero in 2050 metric is a tool that policymakers, the media, business leaders, non-governmental organizations, and the public can use to gauge the adequacy of national policies, spotlight the largest contributors to climate change, and galvanize support to improve the emissions trajectories of those who are off-track.

Among the other breakthroughs are four new air quality indicators that track exposure to sulfur dioxide, nitrogen oxides, carbon monoxide, and volatile organics. New metrics that gauge recycling and ocean plastic pollution have been added to the Waste Management issue category, tracking countries’ efforts to attain closed-loop economies. In recognition of the critical role of agriculture in promoting healthy societies, the 2022 EPI also includes a pilot indicator on sustainable pesticide use.

While the EPI provides a framework for greater analytic rigor in policymaking, it also reveals a number of severe data gaps that limit the analytic scope of the rankings. As the EPI project has highlighted for two decades, better data collection, reporting, and verification across a range of environmental issues are urgently needed. The existing gaps are especially pronounced in the areas of agriculture, water resources, and threats to biodiversity. New investments in stronger global data systems are essential to better manage sustainability challenges and to ensure that the global community does not breach fundamental planetary boundaries.

The inability to capture transboundary environmental impacts persists as a limitation of the current EPI framework. While the current methodology reveals important insights into how countries perform within their own borders, it does not account for “exported” impacts associated with imported products. With groundbreaking models and new datasets emerging, the EPI team has been working to produce new metrics that account for the spillovers of harm associated with traded goods in an interconnected world.

Global pandemic

Economic and societal disruptions stemming from the COVID-19 pandemic continue to add to the challenge of meeting the sustainability imperative. Although remarkable improvements in air quality and reductions in greenhouse gas emissions followed early lockdowns and fundamental shifts in economic activities, these gains came at a terrible cost in terms of human health and economic well-being. Policymakers now have a chance to rebuild their economies and societies on a more sustainable basis that preserves the pandemic-induced gains in environmental health and ecosystem vitality – but the latest data suggest that this opportunity is being squandered across most of the world.

Air pollution has rebounded to pre-pandemic levels almost everywhere, as have many countries’ greenhouse gas emissions. COVID-19 has also pushed the world further away from a circular economy, generating millions of tons of plastic waste as healthcare systems and people consume facemasks, plastic food containers, and personal protective equipment.

Countries’ wealth and environmental performance

While we find a positive correlation between countries’ wealth (GDP per capita) and overall environmental performance, many countries out- or underperform their economic peers.

As with overall performance, wealthy countries score higher across most component indicators. But there is large variation in the magnitude of the average score difference between the wealthiest and poorest countries, and poor countries outperform their wealthier peers in several indicators, especially those related to ecosystem vitality

2022 EPI Framework

The framework organizes 40 indicators into 11 issue categories and three policy objectives, with weights shown at each level as a percentage of the total score.